BUTLER, Pa. — When gunshots rang out at the Trump rally where she was working, Butler Eagle reporter Irina Bucur fell to the ground like everyone else. She was terrified.

However, she barely froze.

Using poor cell service, Bucur tried to text her assignment editor to tell him what was going on. She made mental notes of what the people in front of and behind her were saying. She used her phone to take videos of the scene. Before she felt safe again when she stood up.

When the world’s biggest story came to the tiny hamlet of Butler in western Pennsylvania a week ago, it didn’t just draw media from everywhere else. Journalists at the Eagle, the community’s resource since 1870 and struggling to survive, like thousands of local newspapers across the country, had to make sense of the chaos in their backyard — and the global scrutiny that followed.

Photographer Morgan Phillips, who stood on a dais in the middle of a field with Trump’s audience on Saturday evening, stayed on her feet and continued to work on documenting history. After Secret Service agents pushed the former president into a waiting car, those around her turned and shouted vitriol at the reporters.

A few days later, Phillips’ eyes filled with tears as he recounted the day.

“I just felt really hated,” said Phillips, who, like Bucur, is 25. “And I never expected that.”

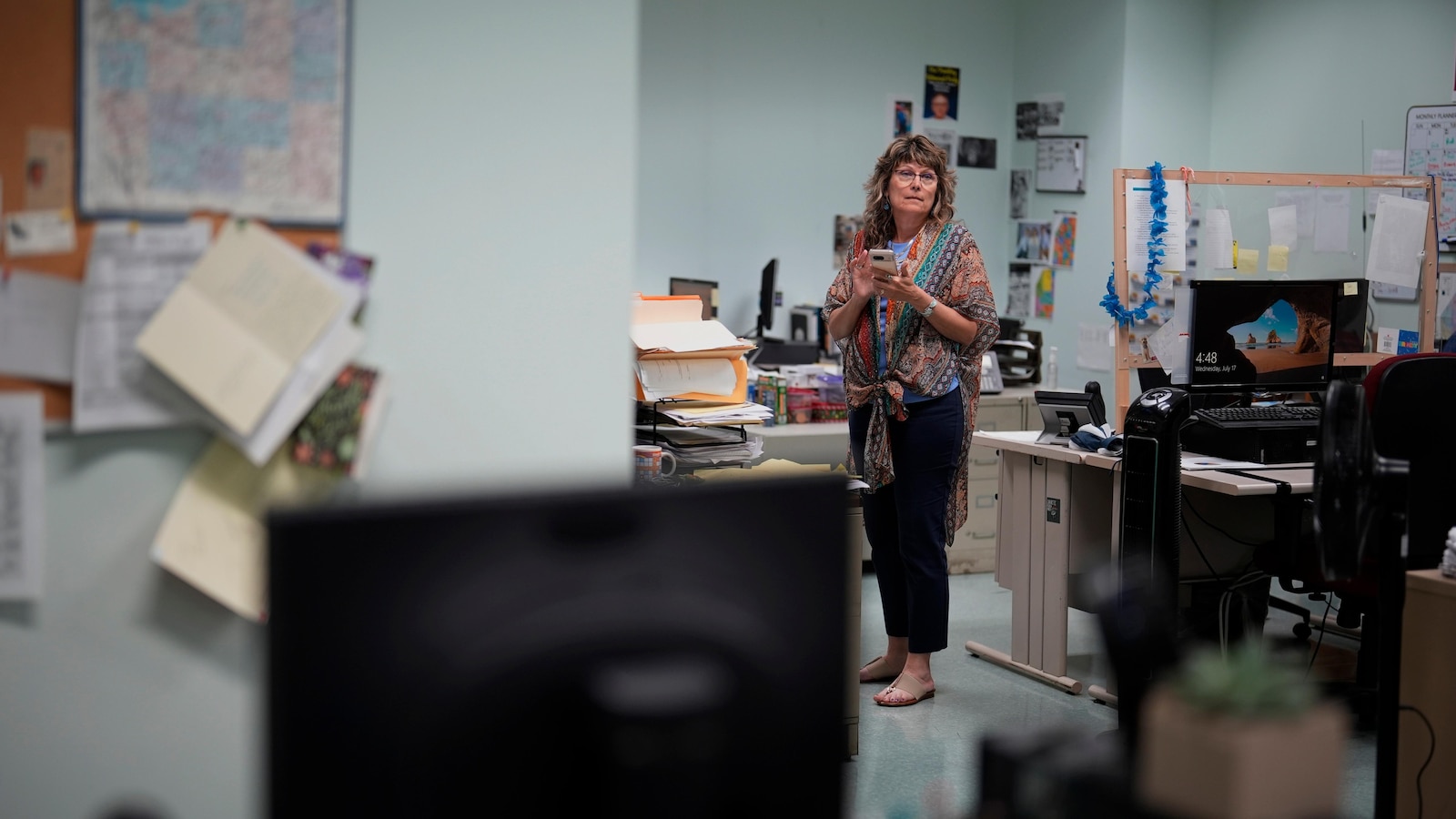

“I take great pride in my newsroom,” said Donna Sybert, editor-in-chief of the Eagle.

After creating a cover plan, she escaped to go fishing with her family nearby. A colleague, Jamie Kelly, called to tell her that something had gone terribly wrong and Sybert rushed back to the newsroom to help update the Eagle’s website until 2 a.m. Sunday morning.

Bucur’s assignment had been to talk to community members who attended the meeting, as well as those who set up a lemonade stand on the hot day and people who parked cars. She had done her reporting and was used to texting updates of what Trump was saying for the website.

The shooting changed everything. Bucur tried to interview as many people as possible. Somewhat dazed after authorities cleared the lot, she forgot where she had parked. That gave her more time for reporting.

“By going into reporter mode, I was able to distract myself from the situation a little bit,” Bucur said. “Once I got up, I didn’t think at all. I just thought I had to interview people and get the story out because I was on deadline.

She and colleagues Steve Ferris and Paula Grubbs were asked to compile their reports and impressions for a story in Monday’s special eight-page print edition of Eagle’s.

“The first few gunshots sounded like fireworks,” they wrote. “But as they continued, people in the crowd at the Butler Farm Show venue fell to the ground: a father and mother told their children to crouch. A young man sat bent over in the grass. Behind him a woman began to pray.”

The special edition clearly resonated in Butler and beyond. Additional copies are available for purchase for $5 in the Eagle’s lobby. That’s already a bargain. On eBay, Sybert said, she has seen them go for up to $125.

In addition to its status as a local newspaper, the Eagle is an endangered species.

It has resisted ownership by a major chain, which has often robbed the news channels. The Eagle has been owned by the same family since 1903; the patriarch, Vernon Wise, is now 95. Fifth-generation family member Jamie Wise Lanier drove from Cincinnati this week to congratulate the staff on a job well done, said general manager Tammy Schuey.

Six editions are printed each week, and a digital site has a paywall that has been lowered for some shooting stories. The Eagle’s circulation is 18,000, Schuey said, with about 3,000 of those being digital.

The United States has lost a third of its newspapers since 2005 as the Internet chews away at once robust advertising revenue. According to a study by Northwestern University, an average of 2.5 newspapers per week will close by 2023. The majority were in small communities like Butler.

The Eagle left a newsroom on the other side of town in 2019 and consolidated space in the building that houses the printing press. The company has diversified, establishing a billboard company and taking on additional printing work. It even preserves the remains of a long-shuttered local circus and offers residents the opportunity to visit.

The Eagle has about thirty employees, although it is now only two reporters and one photographer short. Cabinets of old photos lie between the cluttered desks in the newsroom, with a whiteboard showing which staff members will be on site over the weekend.

The staff is a mix of young people like Bucur and Phillips, who tend to move on to larger institutions, and young people who put down roots in Butler. Sybert has worked at the Eagle since 1982. Schuey was initially hired in 1991 to teach composing room employees how to use Macs.

“This is a challenging undertaking,” Schuey said. “We’re not out of the woods yet.”

When a big story breaks, with the national and international journalists following it, local news outlets are still a precious and valued resource.

De Adelaar knows the terrain. It knows the local officials. Smart national reporters who “parachute” into a small community that suddenly breaks news will look for local journalists. Several have contacted the Eagle, Schuey said.

Familiarity helps in other ways. Bucur found people at the meeting who were suspicious of national reporters but answered her questions, as did some authorities. She has used her network of Facebook friends to reach out for help.

Such fundamental trust is common. Many people in small towns have more confidence in their community newspapers, said Rick Edmonds, the media business analyst at the Poynter Institute.

“It’s just nice to support locals,” said Jeff Ruhaak, a trucking company supervisor, who paused over a meal at the Monroe Hotel to discuss the Eagle’s reporting. “I think they did a pretty good job considering their size.”

The Eagle has another advantage: It doesn’t go anywhere when the national reporters leave. The story will not end. Hurt people need to recover and investigations will reveal who is responsible for allowing a potential killer to take a chance on Trump.

In short: responsible journalism as civic leadership at distressing moments.

“Our community has been through a traumatic experience,” Schuey said. “I was there. We have some healing to do, and I think the newspaper is a critical part of helping the community get through this.

That includes the people at the Eagle, as Phillips’ raw emotions testify. Management is trying to give employees a few days off, perhaps with the help of journalists from surrounding communities.

Bucur said she would hate to see Butler turned into a political pillar, with the killing used as a kind of rallying cry. The divisions in national politics had already filtered into local meetings and staffers have felt the tension.

Sybert and Schuey look at each other to remember the biggest story Butler Eagle journalists worked on. Was it a tornado that killed nine people in the 1980s? A particularly serious traffic accident? Trump made a quiet campaign visit in 2020. But there’s no doubt about what tops the list now.

Despite the stress of the assassination attempt, reporting it has been a personal revelation for the soft-spoken Bucur, who grew up 30 miles (48.2 kilometers) south of Pittsburgh and studied psychology in college. Her plans changed when she took a communications course and loved it.

“This,” she said, “was the moment I told myself I think I’m cut out for journalism.”

___

David Bauder writes about media for the AP. Follow him up http://twitter.com/dbauder.