One of the many heated debates in paleontology is how winged pterosaurs could fly. Some experts speculate that the largest among them may not have even been able to fly at all, similar to today’s ostriches and similar dinosaurs.

Now we’re getting new clues about the different ways pterosaurs got off the ground and into the air, thanks to some well-preserved specimens. Two different species of large-bodied pterosaurs, including one new to science, indicate that some flew by flapping their wings, while others soared more like modern vultures. The findings are detailed in a study published on September 6 in the peer-reviewed Journal of vertebrate paleontology.

[Related: We still don’t know how animals evolved to fly.]

“Pterosaurs were the first and largest vertebrates to evolve powered flight, but they are the only large volant group to become extinct,” said co-author and paleontologist Kierstin Rosenbach of the University of Michigan. said in a statement. “Efforts to date to understand their flight mechanisms have been based on aerodynamic principles and analogy with extant birds and bats.”

Hollow bones

The fossils were first discovered in 2007 by co-authors Jeff Wilson Mantilla of Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology and Iyad Zalmout of the Saudi Geological Survey. The ‘remarkable’ specimens date from about 72 to 66 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous.

Over time, they were preserved three-dimensionally in two different locations of what was once the coastal environment on the edge of Afro-Arabia. This ancient landmass that included both Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, which broke up about 30 to 35 million years ago. Using high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans, the team analyzed the internal structure of the wing bones.

“Because pterosaur bones are hollow, they are very fragile and are more likely to be found flattened like a pancake, if they are preserved at all,” says Rosenbach. “Because 3D preservation is so rare, we don’t have much information about what pterosaur bones look like inside, so I wanted to CT scan them.

According to Rosenbach, it was “quite possible” that nothing was preserved in the bones or that the scanners the team used were not sensitive enough to distinguish fossil bone tissue from the other material surrounding it. Fortunately, they were able to see the well-preserved internal wing structures.

[Related: Dinosaur Cove reveals a petite pterosaur species.]

Fluttering versus floating

One of the specimens collected is of the giant pterosaur, Arambourgiania philadelphiae. The new analysis confirms this approximately 32 feet wingspan and provides the first details of the bone structure. The CT images showed that the inside of the humerus is hollow and has a series of ridges running up and down the bone. This is similar to the inner wing bone of modern vultures. Scientists believe these are spiral ridges resist the burdens that come with rising. When flying, birds employ sustained, powered flight that requires launching and some maintenance.

The other copy was the newly discovered Inabtanine Alarabiawith a wingspan of about 1.80 meters. According to the team Inabtanine is one of the most complete pterosaurs ever found in Afro-Arabia.

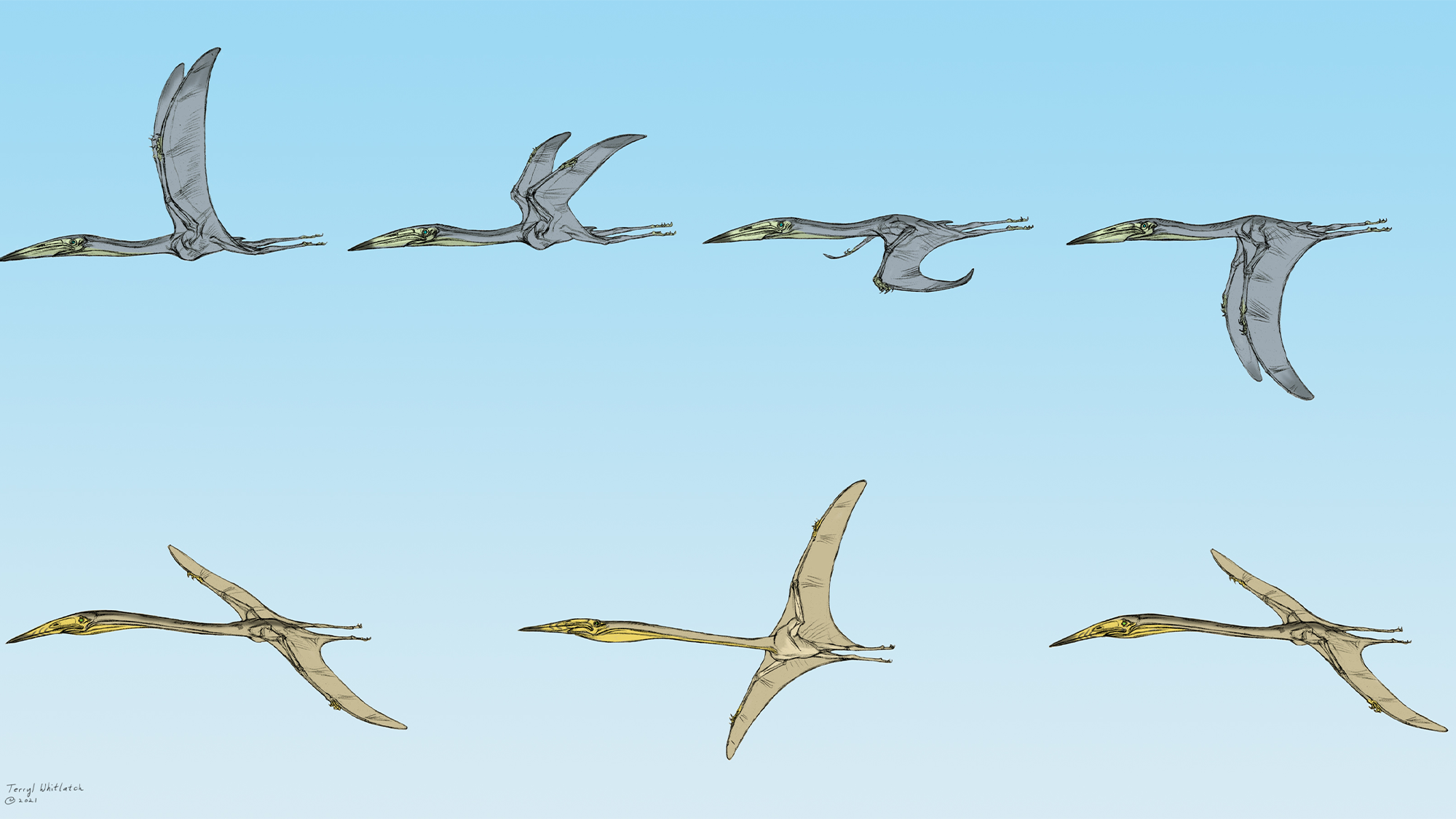

Terryl Whitlatch.

The CT scans showed that the flight bones were built completely differently from those of Arambourgia. The interior of Inabtanin’s were escape bones crossed with struts similar to those found in the wing bones of fluttering birds alive today. This indicates that it is adapted to resist the bending loads in the bone associated with flapping flight. It was probably that Inabtanine flew this way, but may have also dabbled in other flying styles.

“The struts found in Inabtanine were cool to see, but not unusual,” Rosenbach said. “The ridges in it Arambourgia were completely unexpected, we weren’t sure what we were seeing at first! “Being able to see the full 3D model of Of Arambourgia humerus covered in spiral ridges was just so exciting.”

Was flapping the standard?

The team called the discovery of different flight styles in pterosaurs of different sizes ‘exciting’ shows how these animals might have lived. It also raises some questions, including how flight style is correlated with body size and which flight style is more common in pterosaurs.

“There is so little information about the internal bone structure of pterosaurs through time that it is difficult to say with certainty which flight style came first,” says Rosenbach.

[Related: We were very wrong about birds.]

In flying groups of vertebrates, such as birds and bats, flapping is the most common flight behavior. Birds that soar or glide also need some wing beats to get airborne and keep flying

“This leads me to believe that flapping flight is the default condition, and that perhaps flight behavior would evolve later if it were beneficial to the pterosaur population in a specific environment; in this case, the open ocean,” said Rosenbach.

In future studies, scientists could continue to investigate the correlation between a pterosaur’s internal bone structure, their flight ability and behavior.